What makes a good story? I've been asking myself this question my entire career. But instead of studying the meta aspects of what makes a good story, here I am choosing to focus on the aesthetics/mechanics of story structure. Blake Snyder, one of the most revered screenwriting teachers in Hollywood, says that “structure is the single most important element in writing and selling a screenplay” (68). There are several schools of thought on how to structure 90 minutes of story material. But which is the right way or the best way to do it?

Division Into Three Acts

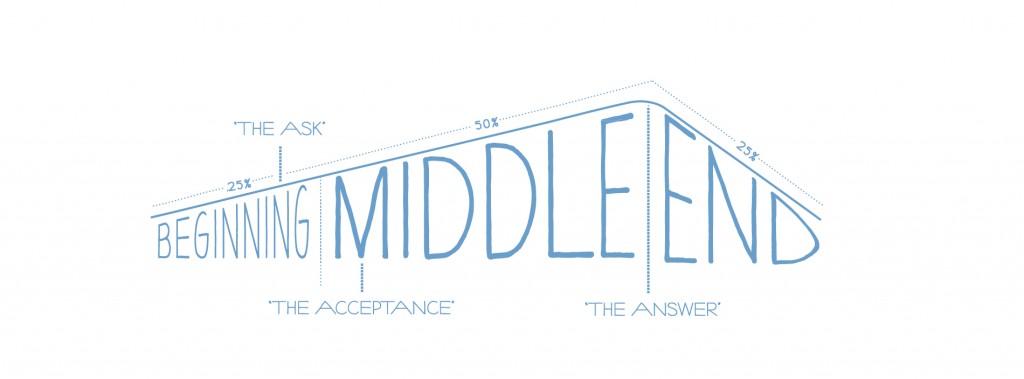

In the skeleton of every story structure, there seems to be a very basic dissection into three major acts: a beginning, middle, and end. “The reason we employ a three act paradigm is that it is the simplest to understand and it most clearly adheres to the phases of an audience’s experience of a story” (Howard & Mabley, 24). Bernard says that this was first articulated by Aristotle: “It describes the way many humans tell and anticipate stories: a setup, complications, and resolution” (58). But even before Aristotle, it was Socrates who developed the 3-part “Socratic Method” of inquiry: thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The ancient Greeks regarded dialogue as a supreme form of art – “the art of discovering truth” (Egri, 51). In Plato’s Dialogues series, documenting some of Socrates’s most profound conversations with Aristophanes and other Ancient Greek students and thinkers, we can see that Socrates paves the way to truth by this process: “he states a proposition, finds a contradiction to it, and, correcting it in the light of this contradiction, finds a new contradiction” (Egri, 51). And this process of contradiction can continue forever. Egri even goes as far as to say that these three steps – thesis, antithesis, synthesis – “are the law of all movement” (Egri, 51). I think he is right. Traces of this basic structure can be found in virtually all temporal art forms, even in music. Many of Mozart’s and Beethoven’s most famous symphonies begin with a single musical theme, melody, or instrument that is then contradicted by an opposing theme or instrument that intertwine and play off each other to progress and develop a completely new theme or melody. And it was Syd Field, my favorite Screenwriting teacher, who said “all drama is conflict”(25). Antithesis = Contradiction = Complications = Obstacles = Conflict = Drama = Storytelling. As mind-oriented beings, we try to dissect, compartmentalize, define, and label everything – the only way to determine where to draw those barriers between one thing and the next is by observing where the shift or contrast occurs. There can be no light without dark, no sky without ground, no space without its container, no room without its walls, no matter without nothingness. This three-step process of communication is how we understand the universe.

But what happens in each act? Simply put, “the first act gets your hero up a tree. In the second act, you throw rocks at him, forcing him higher up in the tree. In the third act, you force him to the edge of a branch that looks as if it might break at any moment.” Then you “let your hero climb down” (Bernard, 55). Screenwriter Syd Field describes Act one as “the set up,” in which “the screenwriter sets up the story, establishes character, launches the dramatic premise(what the story is about), illustrates the situation, and creates the relationships between the main character and the other characters who inhabit the landscape of his or her world”(23). Act two is the “confrontation,” in which “the main character encounters obstacle after obstacle that keeps him/her from achieving his/her dramatic need”(Field, 25). Act three is “resolution” or “solution” of the story, but not necessarily an “ending” (Field, 26). Bernard explains act three further: “the character is approaching defeat; he or she will reach the darkest moment just as the third act comes to a close”(Bernard, 59). But this is not succinct with what other screenwriters have said about the third act. Maybe this was some sort of typo because it makes no sense to me that the protagonist hits a low point just as the third act comes to a close, then suddenly everything is fine and the story ends (unless it is an unhappy ending). According to Blake Snyder the low point usually comes at the end of act two (86), just before a solution is found, then we break into the third act, and the protagonist uses that solution to try to achieve his or her goal one last time – usually ending up successful.

Keep in mind, Bernard’s description was written in a documentary film context. I have found that the paradigms for documentary are a little different, but she also has no mention of any major turning points of a story: midpoint, high point, low point, false victory, reversal, plot points. For example, act one always contains some sort of “inciting incident” (Bernard, 58). Syd Field describes it as “setting the story in motion” (129), which leads us to the first plot point or “key incident, which is the hub of the story line” (133). Each Act is divided by one of these plot points, defined as “any incident, episode, or event that hooks into the action and spins it around in another direction” (Field, 144). “The function of the plot point is simple: it moves the story forward” (Field, 143). There are many plot points scattered throughout a screenplay, but “Plot Points I & II [at the end of the acts] are the story points that hold the paradigm in place. They are the anchors of the story line” (Field, 143). Having no mention of any of these major turning points in a documentary context, I am curious about the structure of some great feature-length documentaries out there. Is the documentary genre exempt from this form/convention?

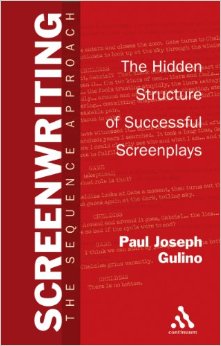

The Sequence Approach

The sequence approach to screenwriting takes this plot point paradigm one step further, breaking a feature-length story into eight sequences of 15 pages/minutes each, “posing a series of dramatic questions within the overall dramatic tension, offer[ing] an opportunity to give the audience a glimpse of a great many possible outcomes” (Gulino, 13). The idea is that each sequence ends with a dramatic turning point, and the story shifts in direction. According to Gulino (my screenwriting professor at Chapman), act one has two sequences. Sequence A answers the “question of who, what, when, where”(Gulino, 14). “By the end of the first sequence, there arises a moment in the picture called ‘point of attack,’ or inciting incident. This is the first intrusion of instability on the initial flow of life, forcing the protagonist to respond in some way” (Gulino, 14). However, Blake Snyder says that the inciting incident or “catalyst” can occur anywhere in the first act or first twenty-five minutes of a film (26). Sequence B “sets up the main tension, posing the dramatic question that will shape the rest of the picture”(Gulino, 15): Will he/she embark on the journey to fix/solve the problem that has thrown his/her world out of whack? Act two has four sequences. Sequence C shows the “first attempt at solving the problem posed at the end of the first act” (Gulino, 15). Sequence D “finds the first attempt at resolution failing” to push the protagonist to “try one or more desperate measures to return his/her life to stability”(Gulino,15). This sequence often leads to a “first culmination or midpoint. This may be a revelation or some reversal of fortune that makes the protagonist’s task more difficult” or a “glimpse at the actual resolution of the picture, or its mirror opposite” (Gulino, 16). In Sequence E, “the protagonist works on whatever new complication arose in at the first culmination” (Gulino, 16). “In some pictures, the experience of the first culmination may be so profound as to provide a complete reversal of the protagonist’s objective” (Gulino, 16). In Sequence F, “having eliminated all the easy potential solutions and finding the going most difficult, [the protagonist] works at last toward a resolution of the main tension, and the dramatic question is answered. The end of the sixth sequence thus marks the end of the second act, also known as the Second Culmination,” giving the audience yet another glimpse of the story’s possible outcomes (Gulino, 17). Act three has two sequences. Sequence G contains the climax and is “often characterized by still higher stakes and a more frenzied pace, and its resolution is often characterized by a major twist” (Gulino, 17). Sequence H “invariably contains the resolution of a picture – the point at last where, for better or for worse, the instability created in the point of attack is settled” (Gulino, 17). These final moments are where the epilogue, coda, or denouement occurs, tying up any remaining loose ends. To me, this is a much more succinct structure method.

The Beat Method

But the beat method takes the sequence method even further. I found all the previous structuring methods to be too generic and basic for me. They still don’t explain what happens when. Coined by Blake Snyder in his book Save the Cat, I found “The Beat Method” to be the most helpful for me in determining a feature-length narrative structure. The idea is based on Snyder’s desire to fit the major beats of any story on one sheet of paper (about 15 beats total). It starts on page 1 with the “opening image,” or the very first thing audiences see to introduce them to the tone and feel of the story. Then the “theme is stated” on page 5, usually a question or statement posed by the main character or supporting character that illuminates the story’s dramatic premise. Also in the first sequence is the “set up,” where the screenwriter introduces the “six things that need fixing” or what is missing in the protagonist’s life. Around page 12 is the “catalyst” (inciting incident) that puts the story in motion. In the second sequence from page 12-25, we witness the protagonist’s “debate”: Will the hero embark on the perilous journey to fix his life and save the girl? Then on page 25, a decision is made, we “break into two” (ACT II break), and the story takes off!

(click to enlarge)

The “B Story” usually begins on page 30 to open the second act, which is the love story in most films. The entire first half of the second act from page 30-55 is where we see the “fun and games” of the story itself. Snyder describes it as providing “the promise of the premise” where we see the same shots used in the trailer. If it’s a film about a lazy/stoner/surf-bum who must learn how to sell knives in order to support his family after his dad loses his job (SHARP), this is the part of the film where we see that lazy surf-bum being accepted to the job, going to training, learning how to sell, making his first phone calls, making his first sale, etc. This section ends with the “midpoint” on page 55, where the stakes are raised, the protagonist experiences a reversal, he/she approaches the point-of-no-return, and we see two possible outcomes to the resolution of the story. Snyder notes that this is usually a point of false victory, where we think the protagonist has everything handled. If the film is a downer with a sad ending, then the midpoint would be the opposite: a “false defeat.” After this culmination, the midpoint is followed by a section that takes up almost the entire second half of the second act from pages 55-75 where the “bad guys close in.” This is where everything starts getting weird, the bad guys regroup, new complications come to light, and we realize that the protagonist actually did not have everything handled like we thought. This leads him/her to the low point on page 75 where “all is lost.” If the midpoint was a false victory, this would be a point of false defeat where we think the protagonist will not actually achieve his goal. This moment is usually abbreviated by some dark symbology known as “the whiff of death” where a character dies, suicide is contemplated, or the protagonist comes home to find his cat dead because he has been gone so long trying to achieve his goal.

The rest of Act II from page 75-85 is characterized by the “dark night of the soul,” or the protagonist’s reaction to his/her low point. This is when the protagonist is stuck on the side of the road with a flat tire screaming, “God, why hast thou forsaken me?” This moment always leads to a sudden “Hazzah!” where the protagonist finally has the solution and we “break into three” (ACT III) on page 85. Once the protagonist has the solution, the rest of the film and all of Act III from pages 85-110 is characterized as the “finale” where the protagonist goes into the final battle, the story climaxes, has a major twist, and finally resolves. The very last beat that Synder has on his beat sheet is the “final image” on page 110, which is most appropriately bookended as the opposite of the “opening image” showing the change that has occurred in the protagonist and his/her life. This beat method made the most sense to me, so I used this structure to “beat out” several drafts of SHARP. Snyder notes that page numbers don’t have to be exact. Some beats can be summed up in a single image, while others are several sequences long.

The Hero’s Journey

(Click to Enlarge)

Even Joseph Campbell’s studies of myth have concluded an archetypal 3-act structure, called “The Adventure of the Hero,” on which most epic stories are based (Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter). His exploration of ancient myths from all around the world has developed a story structure divided into these three acts: departure, initiation, and return (viii). Based on Joseph Campbell’s studies of myth, Christopher Vogler took the hero’s story archetype one step further and determined a structure (also broken into three acts) called “The Hero’s Journey” (30). It begins with the “ordinary world” of the hero in his natural environment, where he receives the “call to adventure” to solve a problem or challenge, then “refuses the call,” but is encouraged by a “mentor” or wise man, who helps him make the decision to “cross the first threshold” into Act II or the “special world” to attempt to solve the problem. In Act II, he experiences many “tests, allies, and enemies” in the special world, until he “approaches the innermost cave”(second threshold or midpoint), where he endures the “supreme ordeal,” and wins the “reward or elixir.” In Act III, he embarks on “the road back” to the ordinary world, where he crosses the third threshold and is “resurrected” or transformed by the experience, and finally “returns with the elixir” or boon to benefit the ordinary world (Vogler, 30). This Hero’s Journey is particularly interesting because it has grown from roots deep in the soil of our ancestry, based on legends and myths that preserve many ancient cultures’ heritages that have been extinct for thousands of years – but they live on in story. Amazingly, The Hero’s Journey describes a story line that is very similar to the beat method, and very easily falls into the structure of three acts and eight sequences. I don’t think this is a coincidence.

Form vs. Formula

There is some debate on when exactly each beat should happen. I was taught in film school that instead of reading a script, producers or studio execs will turn to page 12 and 86 (both major plot points) to see if something major happens on those pages. If not, they throw the script away. WHAT?! That’s ridiculous. But most of Hollywood treats structure like the gospels because it has been so ingrained into our psyche for over a century of filmic storytelling that, without any studying or previous knowledge, audiences know whether or not a film is following this structure because they feel it in the timing. Something just isn’t right, they think. Something should have happened by now. “Aristotle deduces that there is a relationship between the size of the story – how long it takes to read or perform – and the number of major turning points necessary to tell it: the longer the work, the more major reversals”(McKee, 217). McKee continues to say that a story can be told in one act, but it must be short – as much content as a short student film. A story can also be told in two acts, but it also must be short – a TV episode (23min) or two act play (one hour). I’ve noticed that sitting and watching or sitting and readingdoes get a little boring if the direction of the action doesn’t have a major turning point every 15 minutes or pages.

We’ve all been to the movies. And we all know the Hollywood “formula.” Like Fords coming off of a factory line, the stories seem to be all the same. But just like a car has four wheels, doors, a steering wheel, gas pedal, brake pedal, windshield, rearview mirrors, a film has three acts, an inciting incident, two major plot points, a midpoint, low point, climax, and resolution. I used to be vehemently opposed to any “rules” on how a filmic artwork should look and feel. But the paradigm is a “form, not a formula. Just because a screenplay is well structured and fits the paradigm doesn’t make it a good screenplay, or a good movie” (Field, 28). There is a reason that we’ve come to develop such a specific plot structure. “There is something about dramatic structure that seems built into the way we receive and enjoy stories” (Bernard, 55). However, documentary seems to be exempt from this form. “Many documentaries do not fit neatly into this structure, but an approximation of it” (Bernard, 55). Perhaps this is because life does not happen perfectly structured like in a Hollywood film. Life is messy. “There are many ways to create a compelling structural through line in a documentary without going anywhere near dramatic three-act structure” (Bernard, 55). Let’s take a look…

The various story structure methods look like the fit together nicely when lined up chronologically.

Conclusion

Who’s to say what story structuring method is right or best? There are many films that are still able to hold interest with fascinating characters, tone, visuals, and theme, like the work of David Lynch, Alejandro Jodorowsky, P.T. Anderson, Antonioni, Fellini, and Godard. But even the entire documentary genre seems to be able to hold interest without such a structure. There does seem to be similarities in all these methods, but aesthetics are subjective and every story is unique. There is no right or best way to structure the content of a 90-120min story. For SHARP, I used a combination of all these methods.

Works Cited

Bernard, S. C. (2010). Documentary Storytelling; Creative nonfiction on screen. Burlington, MA: Focal Press.

Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Egri, L. (2009). The Art of Dramatic Writing. New York, NY: BN Publishing.

Field, S. (1984). Screenplay. New York, NY: Bantam Dell.

Gulino, P. J. (2004). Screenwriting; The sequence approach. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

Howard, D., & Mabley E. (1993). The Tools of Screenwriting; A writer’s guide to the craft and elements of a screenplay. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

McKee, R. (1997). Story. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers, Inc.

Snyder, B. (2005). Save the Cat. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Vogler, C. (2007). The Writer’s Journey. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Art and Craft. Dir. Sam Cullman. Star. Mark Landis. Oscilloscope Pictures, 2014. VOD.

Cutie & the Boxer. Dir. Zachary Heinzerling. Star. Ushio Shinohara. The Weinstein Company, 2013. Streaming.

Exit Through the Gift Shop. Dir. Banksy. Star. Banksy. Oscilloscope Pictures, 2010. Streaming.

How to Draw a Bunny. Dir. John Walter. Star. Ray Johnson. Palm Pictures, 2002. DVD.

Nanook of the North. Dir. Robert Flaherty. Star. Nanook. Criterion Collection, 1922. DVD.

The Artist is Present. Dir. Matthew Akers. Star. Marina Abramovic. HBO Documentary Films, 2012. Streaming.