I’ve always loved learning, but I never liked school. Why is that? Seems wrong to me. Growth and learning are human needs – we constantly strive to be more, do more, have more. And yet, the place we go to learn is alienating, belittling, unhealthy, dehumanizing, and socially stunted. Perhaps the institutional bureaucracy of “school” may not be the best place for something as organic and human as learning.

What is learning and what is teaching?

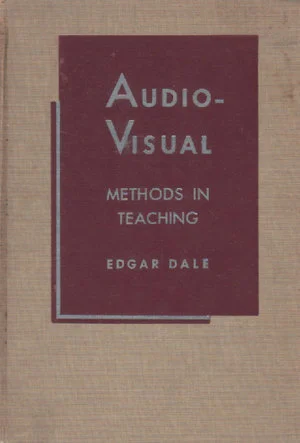

In order to have a better understanding of learning and education, we must first define these terms. American psychologist Abraham Maslow says that “the function of education, the goal of education… is ultimately the ‘self-actualization’ of a person, the becoming fully human, the development of the fullest height that the human species can stand up to” (162). From this perspective, education is supposed to push us to grow personally, the role of the student is to want to grow, and the role of the teacher is to help students grow. The theories of experiential learning proposed by Lewin, Piaget, and Dewey suggest that learning is “a holistic integrative [process] that combines experience, perception, cognition, and behavior” (Kolb 31). Therefore, knowledge is something that “results from the combination of grasping concepts and transforming experience” (Kolb 51). From this perspective, education is a two-step process: First, teachers help students form abstract concepts in the mind, then those concepts are continuously modified by personal direct experiences created by the teacher. Here, the student’s role is to listen and follow with trust and an open mind. Educationist Edgar Dale agrees that one of the main responsibilities given to a teacher is to, “help pupils to attach the right things [to the right] ideas,” so at least half the job of the teacher is to help students form concepts by naming them (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 25). “The overall activity of building concepts, therefore, is a realistic definition of education” (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 26). He argues that “In a civilization as complex as ours, you could not live successfully without abstractions of a high order… But we must never forget that some abstractions are hard to learn and that they must develop out of experience. Mere memorizing of an abstraction or a definition means nothing so far as the power to use it is concerned. And if it cannot be used, has it really been learned?” (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 33).

(click to enlarge)

How does the brain learn best?

This is a puzzling question because everybody learns differently – each brain is wired differently. “The complex structure of learning allows for the emergence of individual, unique styles of learning” (Kolb 100). To tackle this challenge, David Kolb created an individual learning style categorization through a self-assessment questionnaire based on each of the four learning modes – “concrete experience (sample word, feeling), reflective observation (watching), abstract conceptualization (thinking), and active experimentation (doing)” (Kolb 104). But there are so many ways people learn, and not all methods are the most effective for everybody.

I’ve noticed that I cannot comprehend or remember information given to me through reading, unless I interact with it by underlining, highlighting, and notating. I cannot comprehend what is being said when people read aloud from text, unless I am reading along with them. I can, however, comprehend speech through conversation or from oration, but if someone is reading aloud, I have no idea what they are saying. I can’t comprehend or remember audio recordings like podcasts or audio books unless I am active – exercising, using my hands, or driving. I can remember what I write handwritten, but not if I type it. I can ALWAYS remember visuals, space, and emotions. According to Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience, motion pictures are the most effective way to learn through indirect methods, short of first-hand experience. This is true for me because I am a visual person, but also because it utilizes multiple methods of transmission (speech, sound, music, visual, oral storytelling, written text/titles, etc.). Being conscious of your own learning styles paints a picture of how complicated this question is.

In his incredible book Audio Visual Methods in Teaching, Dale poses the question: “Why do students often forget what they are taught?” Studying the personal accounts of students forgetting material, he noticed that we forget when…

(1.) it does not seem important to us

(2.) it is not clear what we are supposed to be learning

(3.) we don’t/can’t make use of it (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 12)

These observations led to an understanding of how to foster the most effective learning: (1.) proper motivation (the why), (2.) clear goals (the what), and (3.) adequate use (the how) (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 13). “When one or more of these parts of the learning process is missing, the chances of forgetting are high” (Dale 13).

What are the most effective ways the brain learns? This is the question I set out to answer. Because of my experience in school, I had a hunch that we don’t learn well through reading and lecture, but much better through other methods that aren’t experienced in school. Based on my research, here are some of the most effective ways of teaching that lead to the highest percentage of assimilation of material over a longer period of time….

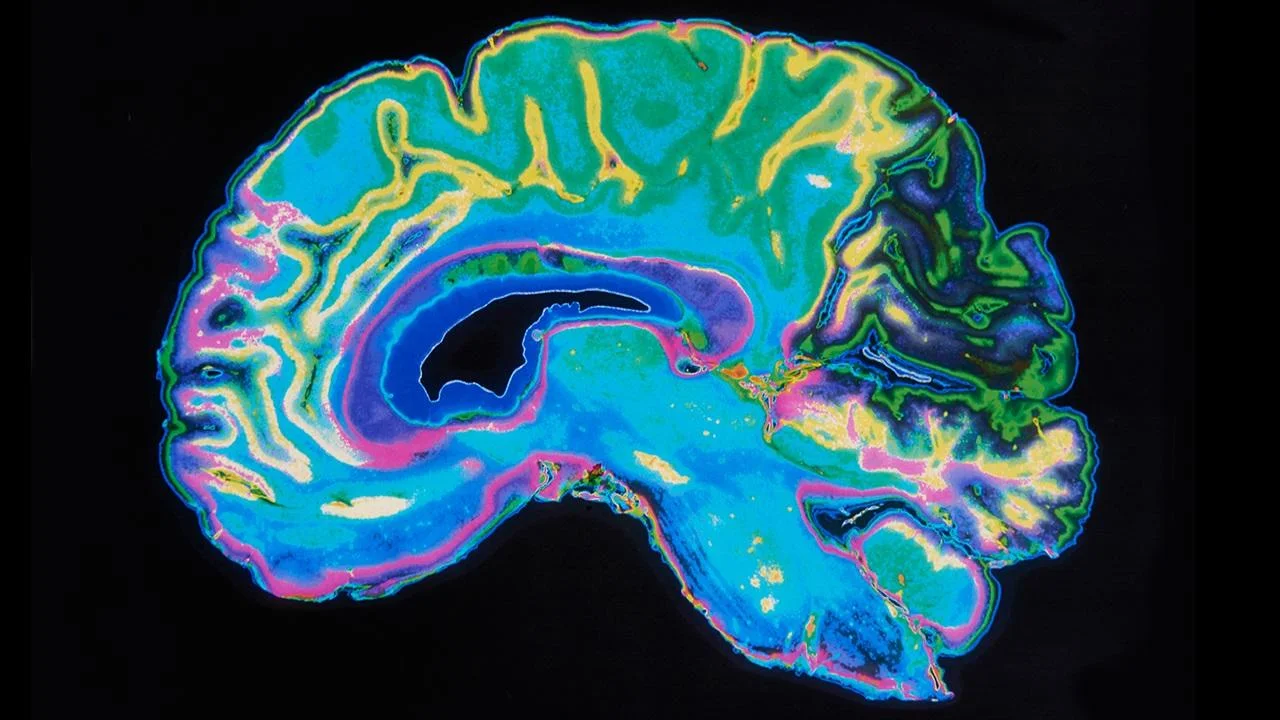

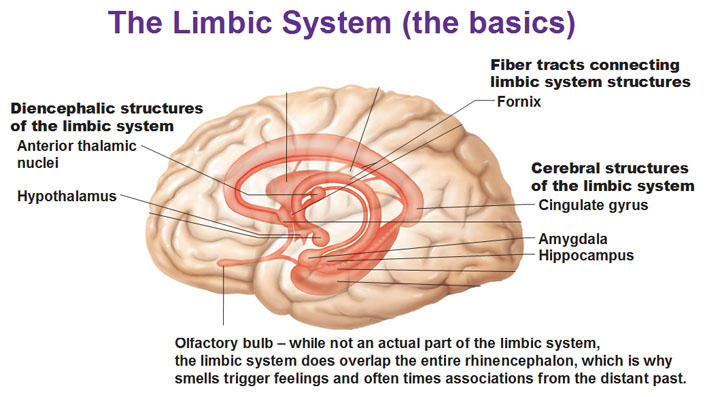

EMOTIONS

Closely attached to the concept of learning is the idea of memory. In fact, both learning and memory come from the same part of the brain: the emotional part. After a few million years with a primitive reptilian brain, the limbic system developed, which gave us emotions. “As it evolved, the limbic system refined two powerful tools: learning and memory” (Goleman 10). But the learning goal should not be to memorize; the learning goal should be to comprehend. The most effective learning should end with assimilation into everyday life to the point of forming a habit. Out of the limbic system, the neocortex developed to give us more complex emotions: feelings about what we think about, feelings about feelings, and even art & creation. But the power of the emotional limbic system still prevails. “Because so many of the brain’s higher centers sprouted from or extended the scope of the limbic area, the emotional brain plays a crucial role in neural architecture…. This gives the emotional centers immense power to influence the functioning of the rest of the brain” (Goleman 9). So because learning and memory both come from the emotional center of the brain, emotions have a way of stamping memories into our consciousness. “…the very same neurochemical alerting systems that prime the body to react to life-threatening emergencies by fighting or fleeting also stamp the moment in memory with vividness” (Goleman 20). Because we are programmed for survival (a program left over from our earlier ancestors), learning from negative/fearful/painful experiences seems to stick more than from positive experiences, but the same imprinting effect happens with all emotional states, whether positive or negative, even “the intense excitement of joy” (Goleman 20). The more emotional the experience, the more it imprints and sticks. That is why “the experiences that scare or thrill us the most in life are among our most indelible memories” (Goleman 21). For this reason, Dale argues that “good teaching involves the feelings as well as the intellect” (Audio Visual Methods, 3). Can you remember the most scared you’ve ever been? And can you remember the most blissful you’ve ever felt? Which can you remember in greater detail?

KINESTHETIC (MOVEMENT)

“The very root of the word emotion is motere, the Latin verb ‘to move,’ plus the prefix ‘e-‘ to connote ‘move away,’ suggesting that a tendency to act is implicit in every emotion” (Goleman 6). Dale adds that “the word motivation has the same root,” therefore a rich experience is a moving experience (Audio Visual Methods, 22). This could explain why we remember body movements more easily than words, symbols, or visuals. “It happens that music, rhythm, and dancing are excellent ways of moving toward the discovering of identity. We are built in such a fashion that this kind of trigger, this kind of stimulation, tends to do all kinds of things to our autonomic nervous systems, endocrine glands, to our feelings, and to our emotions” (Maslow 171). Understanding the power of our emotions from the previous section, perhaps the reason movement helps us learn is because our body is so closely attached to our emotions – we feel emotions in our body, not in our mind. When I run, I listen to podcasts. I seem to remember the material much better than if I sit and listen. I notice that even while sitting, I assimilate audio material much better if I am drawing, using my hands intricately, or even driving. In fact, one of the soundbites that I remember from the Tony Robbins tapes I used to listen to while driving is of him screaming, “Motion creates emotion! Motion creates emotion!”

MOOD

The emotional link to memory is seen further in our emotions’ power to disrupt thought. “Neuroscientists use the term ‘working memory’ for the capacity of attention that holds in mind the facts essential for completing a given task or problem… The prefrontal cortex is the brain region responsible for working memory. But circuits from the limbic brain to the prefrontal lobes mean that the signals of strong emotion – anxiety, anger, and the like – can create neural static, sabotaging the ability of the prefrontal lobe to maintain working memory. That is why when we are emotionally upset we say ‘we just can’t think straight’ – and why continual emotional distress can create deficits in a child’s intellectual abilities, crippling the capacity to learn” (Goleman 27). Therefore, the best cognitive environment for learning is a happy/positive mood. And the best learners are ones who experience less emotional stress throughout their youth. “Healthy people perceive better” says Abraham Maslow (160).

INTRINSIC MOTIVATORS

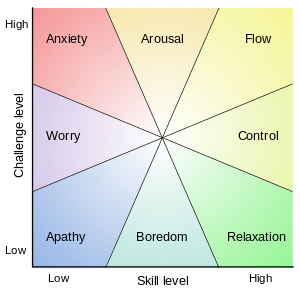

As Dale stated, motivation is a primary determining factor in learning. If a learner is not motivated to learn beyond passing a test or getting a good grade, then all the information retained will float away as soon as the test or class is finished. I’m sure we all have the experience of cramming for a test – do you still remember that information as clearly today as you did the day of the test? I don’t remember any of it. This extrinsic motivation for reward (or to avoid risk) will never be as effective as intrinsic motivation to learn for personal self-fulfillment. What is intrinsic motivation? “Intrinsic motivation must be able to explain behaviors that are motivated by ‘rewards that do not reduce tissue needs,’” such as eating, sleeping, warmth from shelter and clothing, etc. (Deci & Ryan 32). “Intrinsic motivation is based in the innate, organismic needs for competence and self-determination. It energizes a wide variety of behaviors and psychological processes of which the primary rewards are the experiences of effectance and autonomy” (Deci & Ryan 32). For this reason, “many people give up on learning after they leave school because thirteen or twenty years of extrinsically motivated education is still a source of unpleasant memories…. Ideally, the end of extrinsically applied education should be the start of an education that is motivated intrinsically. At that point the goal of studying is no longer to make the grade, earn a diploma, and find a good job. Rather, it is to understand what is happening around oneself, to develop a personally meaningful sense of what one’s experience is all about” (Csikszentmihalyi, 142). “[These] intrinsic needs for competence and self-determination motivate an ongoing process of seeking and attempting to conquer optimal challenges. When people are free from the intrusion of drives and emotions, they seek situations that interest them and require the use of their creativity and resourcefulness. They seek challenges that are suited to their competencies, that are neither too easy not too difficult” (Deci & Ryan 32). Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls this FLOW.

FLOW

Challenge vs. Skill Level in FLOW

Flow is a state of consciousness in which the brain is completely engaged and focused on the task at hand because it is optimally challenged for its skill level. We’ve all experienced flow: your surroundings disappear, you move through time differently, all stresses fade away, focus and calm increase. Csikszentmihalyi studied artists, entrepreneurs, and athletes during their process to find that the emotions associated with flow include joy, bliss, and euphoria.

“Just as flow is a prerequisite of mastery in a craft, so too with learning” (Goleman 93). “Howard Gardner, the Harvard psychologist who developed the theory of multiple intelligences, sees flow, and the positive states that typify it, as part of the healthiest way to teach children, motivating them from inside rather than by threat or promise of reward” (Goleman 94). Indeed, “students who get into flow as they study do better, quite apart from their peers as measured by achievement tests” (Goleman 93). So how can we use the benefits of flow in education? Gardner proposes: “We should use kids’ positive states to draw them into learning in the domains where they can develop competencies” (Goleman 94). Maslow also talks about the value of learning while in PEAK experience (this can most closely be compared to flow): “We may be able to use those experiences that most easily produce ecstasies, that most easily produce revelations, experiences, illuminations, bliss, and rapture experiences. We may be able to use them as a model by which to re-evaluate history teaching or any other kind of teaching” (Maslow 172).

“FOLLOW YOUR BLISS”

Engagement Levels Leading to Behavioral Outcomes

Piggybacking off of the research done on flow and mood, Goleman says “you learn at your best when you have something you care about and you can get pleasure from being engaged in” (94). “That initial passion can be the seed for higher levels of attainment, as the child comes to realize that pursuing the field – whether it be dance, math, or music – is a source of the joy and flow” (Goleman 95). Conversely, “it is when kids get bored in school that they fight and act up, and when they’re overwhelmed by a challenge that they get anxious about their schoolwork” (Goleman 94). This is where I feel very lucky. In middle school and high school, I was taking all honors and A.P. classes, but my days were filled with homework – I would literally get home, start doing homework, and not finish until dinner or later. I had no time to myself. Right around this time, I discovered filmmaking. It was a passion unlike anything I had ever felt – I knew I would be doing it for the rest of my life. So, with the support of my father, I dropped all my honors and A.P. classes (except Calculus because I loved it so much) and focused almost all of my time on making films. I was so motivated to make time for my filmmaking that I would finish all my homework in the library during lunch so I could go to the Digital Media room everyday after school where I worked until around 5PM. I found my purpose, I found my clique, and I thrived.

APTITUDE

Taking the idea of educational flow and passion one step further, “The strategy used in many of the schools that are putting Gardners’ model of multiple intelligences into practice revolve around identifying a child’s profile of natural competencies and playing to their strengths… Knowing a child’s profile can help a teacher fine-tune the way a topic is presented to a child and offer lessons at the level that is most likely to provide an optimal challenge. Doing this makes learning more pleasurable, neither fearsome nor a bore” (Goleman 94). We know that everybody learns differently. So how do we use this to our advantage in education? Some comprehend and retain more through audio listening, some through visuals, some through reading, but most through experience and more creative methods. Therefore, lessons must be tailored to a child’s aptitude and learning style. Musicians will probably learn best through audio or aural methods. Visual artists may learn best through visuals, graphs, charts, etc. Kinesthetic learners will learn better through movement and doing.

SENSUAL STIMULI

“The world of the child, particularly in the elementary school, is a sensory-motor world; he[she] is interested in things that he[she] can see, hear, touch, taste, plan, make, do, and try” (Dale 17). For this reason, the sweet, smooth, euphoric memory of an ice cream cone is more memorable than math class. Something as sensual as ice cream is dangerous – a child’s first ice cream can lead a lifetime of joy, addiction, or even diabetes. “We must not forget that [kids] have eyes, ears, noses, and muscles, and they like to use them” (Dale 20), but I think this is true for all humans. We are sensory beings, and we often obey our senses and emotions more than logic.

Professor Richard Meyer conducted an interesting experiment in the classroom. He divided the class into three sections, one receiving information through one sense (maybe hearing), another receiving information through another sense (maybe seeing), and the third group receiving information in a combination of the two previous sensual methods. What he found was that “The groups in the multi sensory environments always do better than the groups in the unisensory environments. They have more accurate recall. Their recall has better resolution and lasts longer, evident even 20 years later” (Medina 207). Even problem-solving improves. “In one study, the group given multi sensory presentations generated more than 50 percent more creative solutions on a problem-solving test than students who saw unisensory presentations. In another study, the improvement was more than 75 percent!” (Medina 208). Even more surprisingly, “the benefits of multi sensory inputs are physical as well. Our muscles react more quickly, our threshold for detecting stimuli improves, and our eyes react to visual stimuli more quickly” (Medina 208).

Going back to emotional imprinting, extreme sensual experiences can even traumatize the brain to the point of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (P.T.S.D.). After interviewing Holocaust survivors, “about 60 percent said they thought about the Holocaust almost daily, even after a half century” (Goleman 202). P.T.S.D. memories come back as “intense perceptual experiences – the sight, sound, and smell of gunfire…” (Goleman 201). “These vivid, terrifying moments, neuroscientists now say, become memories emblazoned in the emotional circuitry. The symptoms are, in effect, signs of an overaroused amygdala impelling the vivid memories of a traumatic moment to continue to intrude on awareness” (Goleman 201). “The more brutal, shocking, and horrendous the events that trigger the amygdala hijacking, the more indelible the memory” (Goleman 203). To this day, I still can’t walk on grass barefoot.… When I was about five years old, I was running barefoot through the grass to the pool, and I stepped on something – probably a bee or a hornet. I got stung and it shocked me so badly that it still affects my behavior twenty years later.

As previously mentioned, negative/traumatic emotions may brand our memories more than positive ones. But if this branding happens with extreme emotion in general (either positive or negative), then how can we traumatize the brain with positive memories rather than negative ones? Science tells us that it is possible. There are gaps in my memory of my childhood that span for years (I didn’t have the most pleasant childhood, which we’ve learned makes it difficult to learn and form memories). But I do remember my very first solo violin recital and how nervous I was. I remember the dark closet I was in, crying, scared to death. I remember how everybody’s eyes followed me as I walked to the stage, I remember missing the accompanying piano cue once (we had only rehearsed together once). But I also remember the standing ovation that I got when I finished the recital, and how accomplished I felt. I remember the first sales demonstration of my life – I remember how embarrassed and nervous I was to be trying to sell knives to my friend’s parents. I remember how awkward it was when I asked them for the phone numbers of their friends, and how uncomfortable they got, shifting in their seat. But I also remember winning the Sales Rep Champion trophy at the end of that summer. I remember the huge conference ballroom filled with 500 young college-aged sales reps, I remember the giant chandeliers, I remember the girl that I beat by $3,000 and the tattoos on her arms. I remember stepping back and putting my arms in the air when my entire sales team jumped out of their seats screaming. Emotions brand memories into our consciousness forever – both positive and negative.

Here, I think of Tony Robbins’s fire walk. At the end of Tony Robbins events, he has the entire audience (usually several thousand) wait in line for hours to walk across a burning pile of coals, one at a time – it is a test of all the programming he has taught throughout the entire event. Based on the way the brain learns, it is the perfect sensual experience (heat, light, smoke, burning smell, fear) to brand the wisdom and personal growth that an audience member has experienced at a Tony Robbins event into their consciousness forever. My clients are beginning to do the same thing at their events for the same reason. How can we have people suffering from P.T.S.D. after school?

REPETITION / CONDITIONING

“When someone learns to be frightened by something through fear conditioning, the fear subsides with time. This seems to happen through natural relearning” (Goleman 207). For example, “a child who acquires a fear of dogs because of being chased by a snarling German shepherd gradually and naturally loses that fear if, say, she moves next door to someone who owns a friendly shepherd, and spends time playing with the dog” (Goleman 207). So we can assume that the same thing happens with all memories: material can be learned by repetitive conditioning. “Extinction of the fear, appears to involve an active learning process, which is itself impaired in people with P.T.S.D., leading to the abnormal persistence of emotional memories” (Goleman 207). In effect, the event was so traumatic that it literally changed the neural pathways INSTANTLY and created a black hole in the brain that would appear to be PERMANENT. However, “the brain changes in P.T.S.D. are not indelible, and people can recover from even the most dire emotional imprinting – in short, that the emotional circuitry can be reeducated” (Goleman 208). So can we use conditioning to learn? Of course!

Simply Blimpie National Spot – 2001

Here, I remember the Simply Blimpie commercial from the early 2000’s. Simply Blimpie is a sub sandwich shop chain like Subway. When they first started, they launched a national ad campaign on T.V. explaining their marketing strategy. As the spokesman is cutting deli meat, he speaks directly to the camera, “Our marketing team tells us that repetition is a great way to help our customers remember our name.” He continues to cut meat, staring straight into the camera without saying a word, until we notice that his arm repeatedly reveals Simply Blimpie logo on his shirt, over and over again. Repetition has been used in advertising for ages. We’ve all seen the informercials with the fast-talking voice over that repeats the phone number ten times, “Call now!” I still remember the Simply Blimpie commercial to this day, even though I’ve never had a single Blimpie sub.

GAMES

Games are categorized in Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience as “simulation,” which is one of the best ways to remember, as we retain 90% of what we simulate, do, or experience directly. But something else interesting happens when we simulate… In 1989, Patrick Purdy, who had a long history of criminal activity, went to Cleveland Elementary school in Stockton, CA during recess with a semi-automatic rifle and unloaded 106 rounds into a crowd of children, killing five, and wounding 32. This horrific event was branded into the surviving students’ and teachers’ memories forever, which became evident by the students’ behavior as the school year went on. Some students refused to go outside during recess. But astoundingly, others embraced the blood-stained playground by playing a game they called “Purdy,” in which they pretended to be the gunman, shooting each other. Sometimes the game ended with the students dying, but sometimes the students turned against the gunman and shot and killed him/her instead. “One way the emotional healing seems to occur spontaneously – at least in children – is through such games as Purdy. These games, played over and over again, let children relive a trauma safely, as play” (Goleman 208). It is a horrifying image to see children playing a game based on such a horrific event, but because of this, children seem to “less often become numb to the trauma… because they use fantasy, play, and daydreams to recall and rethink their ordeals. Such voluntary replays of trauma seem to head off the need for damming them up in potent memories that can later burst through as flashbacks” (Goleman 209).

DIRECT EXPERIENCE or LEARN-BY-DOING

It was Dewey who first called for a theory of experience in modern education in the 1930s. In his most concise argument, Dewey underscores the value of experience as “continual”: “From this point of view, the principle of continuity of experience means that every experience both takes up something from those which have gone before and modifies in some way the quality of those which come after” (Dewey 35). Therefore, the learning goal should not be assimilation through memorization because this learning stops in the mind. To completely assimilate a material, it must be to the point of understanding it on every level of being, where it changes the learner to the point that it is acted upon in everyday life and becomes habitual. “The basic characteristic of habit is that every experience enacted and undergone modifies the one who acts and undergoes, while this modification affects, whether we wish it or not, the quality of subsequent experiences. For it is a somewhat different person who enters into them” (Dewey, 35). Dewey further states that the point of education should be growth (not only intellectually, but also physically and morally), and is exemplified by the principle of continuity (Dewey 36).

Edgar Dale followed Dewey with his Cone of Experience (Cone of Learning) in the 1950s, suggesting that learning through direct experience, or learning by doing, is the MOST effective way to learn. “The root of the word experience comes from expereri, meaning to ‘try out.’ When we try out things, we must be active not passive” (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 21). Studying the accounts of hundreds of students’ most vivid memories, he found that they were all rich and meaningful events in the life of the reporter. Therefore, “education must become the rich, active, personal, and adventuresome thing it is when a father teaches his son how to fish, or a mother teaches her daughter how to bake a cake, or a scout leader explains to youngsters how to find their way in the woods without a compass, or a dramatic teacher coaches a play. For in all these situations learning has motivation, clarity, and [purpose] to such a degree that permanence can almost be taken for granted. It has, in addition, a train of other qualities – such as pleasure, emotional gratification, and a sense of personal accomplishment – which strongly reinforce learning” (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 19). Dale goes further, using students’ first-hand memories to define a rich experience as one that is sensual, one that brings imagination into reality, a sense of newness, a feeling of discovery, emotional, a feeling of personal achievement(Audio Visual Techniques 19-22).

OTHER METHODS…

Socrates, famous for The Socratic Method

There are many more methods of learning and teaching than I can probably list. For example, Edgar Dales says, “Real learning places the emphasis not on parroting or memorizing book statements but on evaluating them – on relating them to what we already know and on using them as part of our daily life” (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 14). Therefore, learning comes in reflection, through writing, thinking, or discussion. Because learning is a process, knowledge and wisdom cannot be assimilated just by memorizing it. Assimilation can only come in reflection upon the material – creating your own ideas about it. We also know from one of the best teachers of all time that questioning in The Socratic Method is an effective way to teach and to learn. This may be because it allows students to reflect. In addition, Dale lists Collaborative or Group Learning as an effective method. This is one strength that our current education system has because of “grade levels,” which group students together by age and intellect into classes where they learn together. But the last great way to learn is to teach. Einstein once said, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” You will never know a material or subject as well as you do when having to teach it. And having an understanding of how the brain learns, you should now be able present and teach material effectively. But don’t choose just one method and stick with it. Remember, everybody learns differently. The best teachers have an understanding of all styles of learning, and coupling with the concept of repetition/conditioning, use multiple methods to allow all the students to assimilate the information the most effectively.

My research has taught me that some of the best ways to learn and teach are to use multiple methods like visuals, reflection, and teaching. Edgar Dale fights for the use of audio visual methods in his incredible book Audio Visual Methods in Teaching, which has probably informed my art practice more than any other book I’ve ever read. So, in the spirit of learning and teaching, here is an attempt to visually diagram how the brain learns best, based on all my research:

Ways the Brain Learns Best

But how do we learn in schools?

Now that we know how the brain learns best, it is important to note how we learn in schools. Do you remember using any of the aforementioned methods in your schooling? I don’t. While crashing a curriculum meeting at a local high school, Edgar Dale noticed that “not a single teacher or administrator present ever suggested that high school in itself had anything to do with rich and intelligent living, with health, with fine arts, with civic participation, with economic competence, with actually doing something in concrete life situations” (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 3). Schools today require students to memorize material, usually in the form of reading and listening to teachers lecture (which according to Edgar Dale are two of the most ineffective methods of retaining information). Then they are tested on their ability to memorize such material by regurgitating it on a test or exam. “We have been asking [the student] not, ‘What can you do?’ but ‘What do you remember?’ And as we have all come to realize, education involves the ability to make experiences usable” (Audio Visual Techniques 50). By the end of a semester, students are assessed on their overall ability to remember the subject material by being given a grade: A, B, C, D, or F for “fail.” What this result-oriented process of education does is make the material meaningless in life, and only meaningful to getting a good grade. Once that result is achieved, the information is lost forever. “There are those who feel that the orientations that conceive of learning in terms of outcomes as opposed to a process of adaptation have had a negative effect on the educational system. Jerome Bruner, in his influential book, Toward a Theory of Instruction, makes the point that the purpose of education is to stimulate inquiry and skill in the process of knowledge getting, not to memorize a body of knowledge. ‘Knowing is a process, not a product’” (Kolb 38).

I’m sure we’ve all had the experience of cramming for a test the night before. It is an effective strategy for passing tests, but the information is only retained in our “working memory,” otherwise known as our short term memory (Medina 209). Paulo Freire calls this model “banking.” “Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat” (Friere, 58) in (Kolb, 38). Why does the brain not retain much through reading and listening? Because verbal methods of communication require the brain to first interpret the abstract symbols (letters, words, sentences) of our language. While the understanding of a direct experience is inherent; there is no need for interpretation, and the download is immediate (Dale, Audio Visual Methods, 52).

It is also important to note the top-down power structure in today’s educational institutions. Have you ever had a teacher who desperately needed to impart his/her authority over the classroom and students? I’ve been sent to the principal’s office way too many times to not understand that adult teachers need to feel like they are in control, which seems erroneous from a child’s perspective. “Classroom learning often has its unspoken goal the reward of pleasing the teacher. Children in the usual classroom learn very quickly that creativity is punished, while repeating a memorized response is rewarded, and concentrate on what the teacher wants them to say, rather than understanding the problem” (Maslow 174). As a result, “Probably half of the 60,000,000 kids who attend school in the United States, removed from their own families at a very vulnerable age, become emotionally dependent on a pat on the head, a smile, avoiding an insult” (John Taylor Gotto, Human Resources; Social Engineering in the 20th Century). Therefore, teachers and administration have the power, while students do what they are told, or are punished. How does this support learning? And how motivated are teachers to do their job effectively? Learning may be the most important skill one has, especially as our culture gets more and more complicated and sophisticated. And yet, teachers get paid so little. Meanwhile, doctors get paid handsomely for prescribing pills that do not fix our ailments, and only lessen the symptoms. It is a strange system, indeed.

What do we learn in schools? And more importantly, what do we not learn?

“Altogether, too many of [the subjects] have importance only in the eyes of the teacher and within the four walls of the schoolroom” (Audio Visual Techniques 2). How is the information used in the real world? I remember one of the biggest criticisms my peers had of the cliché subject units like language arts, advanced mathematics, and history, was that the information had no practical use in modern life. “The subject matter of education consists of bodies of information and of skills that have been worked out in the past; therefore, the chief business of the school is to transmit them to the new generation…. Learning here means acquisition of what already is incorporated in books and in the hands of the elders…. Since the subject matter as well as standards of proper conduct are handed down from the past, the attitude of pupils must, upon the whole, be one of docility, receptivity, and obedience…. The traditional scheme is, in essence, one of imposition from above and from outside” (Dewey, 17,18,19). Imposition is the opposite of individuality, external discipline is the opposite of free activity, learning from texts and teachers is the opposite of learning through experience, memorization is the opposite of comprehension, and preparation for a remote future (college and career prep) is the opposite of living in the moment, which are all the most important ways of not only learning, but of BEING (Dewey, 19).

So if school does not present material in the most effective ways, then what does our current educational system really teach students? We know that it teaches students how to memorize for the short term, how to pass tests, how to please the teacher, how to conform, how to do what they’re told, how to shut up and listen. Some valuable wisdom can come from these lessons. The real educational values of school lie in social learning – how to be social, what is socially acceptable, how to interact with others, etc. I was one of the many awkward young students who missed out on this lesson, so that proves that throwing students in a classroom together does not ensure they will learn how to get along and collaborate effectively. These are indeed valuable lessons. But is this the real point of education and learning?

Here’s what we DON’T learn. We don’t learn about money (though we use it everyday) and now are in the most debt we’ve ever been in as individuals and as a nation. We don’t learn about health or food while the food served in schools is atrocious and nutritionally barren and adult obesity has now reached 35% (U.S. Department of Health). We do not learn how to learn, just to memorize. Learning is an invaluable skill that would help us cultivate a learning attitude for the rest of our lives. We do not learn how to be creative, which is another invaluable skill in solving problems. But most of all, we do not learn about ourselves. There are no aptitude tests to communicate what a student’s personal interests and skills are. There are no aptitude tests to profile a student’s individual learning style. HOWEVER, public education is free and provides a very basic level of learning. We all know, “You get what you pay for.” But it is a level of learning that is needed to just survive, not to thrive.

Why has it not changed?

John Dewey criticized the American education system in the 1930s as being too lacking in experience. Then Edgar Dale criticized the education system in the 1950s for being ineffective given the knowledge we have about how the brain learns. So why hasn't our education system changed yet?

It is important to note here how teachers learn. When I meet professionals in the education industry, I always ask about educationists like Edgar Dale, John Dewey, Piaget, Kolb, and even Mihaly, etc. But I have never met a single educator who knows these thought leaders. This blows my mind! What the heck do they learn at teacher school? Why are they not learning how the brain learns? Because the curriculum for teachers-in-training is to learn how to deliver the curriculum created by the state, not to learn how to teach.

Most faculty members would probably argue that it is due to “budget cuts.” Budget cuts have become the scapegoat in public education. “If methods other than reading are effective, why are book-reading and book-recitation so commonly used in schools? Why has this procedure retained its hold, if it has the weaknesses discussed? (Audio Visual Techniques 50). “To answer this question, you must remember that through almost all of human history, people have learned by direct experience and by stories passed down from one generation to another. The son learned to make shoes by apprenticeship to his father, the daughter helped her mother spin and weave. It is only in the last century that book-reading has become a common learning method for wide sections of the population…. Textbooks are commonly used because they offer a means for teaching the vastly increased numbers of pupils in school” (Audio Visual Techniques 50). So it may be more of an issue of efficiency and mass-production to meet the needs of millions of students, rather than the concern for what and how the next generation is learning. HOWEVER, when Edison first invented the moving image medium, he actually predicted its value in education: “The only textbooks needed will be for the teacher’s own use. Films will serve as guide posts to these teacher-instruction books, not the books as guides to the films. Pupils will learn from films everything there is in every grade from the lowest to the highest… Films are inevitable as practically the sole teaching method” (Audio Visual Techniques 183). Indeed, the motion picture is much more effective than the textbook, but it is also more scalable than printing a book, especially today. But again, why have moving images not replaced the textbook or at least been used in schools more?

It is important to understand that the government pays for our public education system. If they wanted talented, creative, problem solvers to fix our world, they’d begin teaching entrepreneurial, engineering, and problem-solving skills early on. If they wanted to continue to grow and advance as a culture, they’d support experimentation, new ideas, and new programs. But they don’t. So what is it that they really want our children to learn? What is it that they want our children to be? This is the million dollar question.

The documentary film Social Engineering in the 20th Century suggests that our education system is designed to create middle class factory workers for a world that is no longer essentially industrial. This is why students learn to conform, be obedient, not challenge authority, to wake up early, to work on a schedule. Even the bell schedule system is reminiscent of 1950s factories, modeling Pavlov’s bell conditioning. This calls for a shift in the educational system. Our children are not factory workers. Our children are our future.

“What are we trying to do? If our goal is to help our kids become critical thinkers, lifelong learners who really enjoy thinking and reading and playing with numbers and ideas… if we want to help them become good learners and good people who can create and sustain a functioning democracy, then education would be very different than it looks right now in our culture. We would question the use of grades. What research finds is that when kids are trying to get good grades in school, three things tend to happen. They begin to lose interest in learning itself, now their purpose is just to get a good grade rather than to engage with the question or problem at hand. Second, they tend to think less deeply and retain knowledge for a longer period of time compared to kids who don’t have any grades. Third, they tend to pick the easiest possible tasks. It’s not because they’re being lazy, it’s because they’re being rational”

To this day, I am still trying to get rid of the conditioning that I was imbued with for 20 years. Go to school, get good grades, go to a good college, get a degree, get a good paying job, do what you’re told, don’t be loud, don’t stand out, etc. Ever since graduating college, the rebel within me has pushed me to avoid this path thankfully. But what can we do about this? The future of our children and our country is at stake. Without effective learning, we will be stuck in the same hamster wheel forever. I think it’s clear now that government cannot help solve our problems. We must take things into our hands, not by voting in a system that is fixed, but instead by choosing our own paths and voting with our dollars. Unless our education system changes, I personally plan on home-schooling my kids and finding social activities for them to learn usable social skills. Have you ever met a home-schooled child? The home-schooled kids that I’ve met are amazingly bright and relaxed. Then after high school, I like the idea of teaching them valuable real-world skills (envisioning, selling, creative problem-solving, planning, personal growth, leadership, money, business, helping people, and adding value) by spending $200,000 on a business idea of theirs instead of tuition. The money seems better spent. In my writing I have asked many questions without presenting possible answers because like Socrates, I believe one of the main goals of education is to inspire thinking and the personal pursuit of your own answers and knowledge. So what will you do with your kids?

Bibliography

Blumer, Herbert. Movies and Conduct. Vol. 8. New York, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1933. Print. 12 vols. Motion Pictures and Youth; The Payne Fund Studies.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1990. Print.

Dale, Edgar. Audio Visual Methods in Teaching. New York, NY: The Dryden Press, Inc., 1946. Print.

---. The Content of Motion Pictures. Vol. 9. New York, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1935. Print. 12 vols. Motion Pictures and Youth; The Payne Fund Studies.

Deci, Edward, and Richard Ryan. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press, 1985. Print.

Dewey, John. Experience & Education. New York, NY: Free Press, 1938. Print.

Goleman, Daniel. Emotional Intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Dell, 1995. Print.

Kolb, David. Experiential Learning. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc., 2015. Print.

Maslow, Abraham. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York, NY: Penguin Group, 1976. Print.

Medina, John. Brain Rules; 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School. Seattle, WA: Pear Press, 2014. Print.